Some cool die casting china images:

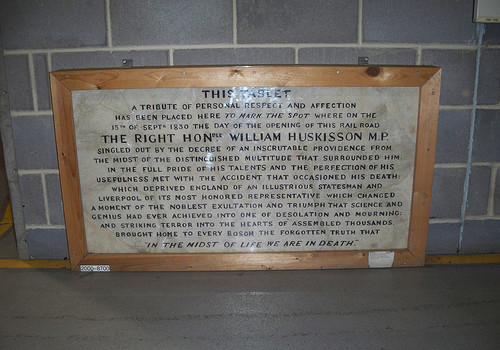

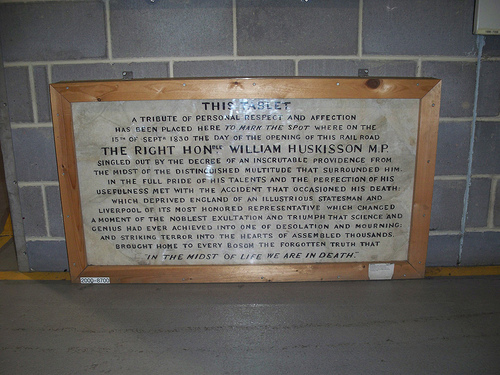

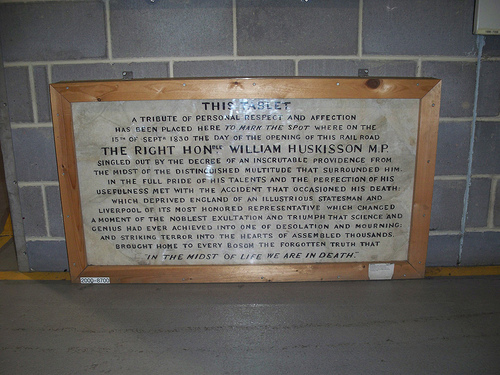

William Huskisson M. P. plaque – National Railway Museum, York, England

Image by Bolckow

From Public Sculpture of Sussex

"On 15 September 1830, at the opening ceremonies for the world’s first ever passenger steam railway (in between Liverpool and Manchester), Huskisson was run over and killed by Stephenson’s Rocket because he had not taken adequate care prior to crossing the track to start a conversation with the Duke of Wellington. He lived for a handful of hours right after the accident, was lucid enough to dictate and sign a codicil to his will, and met his finish with dignity.

He had been politically instrumental in bringing about the new and quite visible triumph of technology that was the Liverpool and Manchester railway line.

William Huskisson was born in Worcestershire in 1770. In 1793 he entered parliament as MP for Morpeth, Northumberland. In 1804 he was elected for the constituency of Liskeard and became Secretary of the Treasury. He held the identical appointment in Portland’s ministry of 1804-09. In 1811 he became a Commissioner of the Woods and Forests. In 1823 he was appointed as President of the Board of Trade and Treasurer of the Navy in Liverpool’s ministry. Below Wellington he was Colonial Secretary but resigned in 1828.

Huskisson had threatened to resign on a number of occasions. Wellington might have been entirely wearied by Huskisson’s continuous threats to resign. Huskisson’s tendered his resignation more than what was to be accomplished with the two parliamentary seats that were to be disenfranchised for corruption in 1828 (Penryn and East Retford) – not expecting his resignation accepted. Wellington maybe was glad of an excuse to eliminate him.

Charles Greville wrote about Huskisson, soon after his death:

Huskisson was about sixty years old, tall, slouching, and ignoble-seeking. In society he was really agreeable, without having significantly animation, generally cheerful, with a fantastic deal of humour, data, and anecdote, gentlemanlike, unassuming, slow in speech, and with a down-cast look, as if he avoided meeting anybody’s gaze. … As a speaker in the Property of Commons he was luminous upon his own subject, but he had no pretensions to eloquence his voice was feeble, and his manner ungraceful…

[Greville Diaries, 18 September 1830]

There was a equivalent monument of Huskisson in his toga at the top of Princess Avenue, Liverpool. Right after the riots of 1981 the bronze statue, some 10 to 15 foot tall, was pulled down by people who believed he was a slave trader. Harm was sustained, the head was practically smashed off. It lay unceremoniously in a council auto park till 1984. The statue is now housed at the Oratory, St James’s Mount Gardens. Another statue of Huskisson, dressed in a Roman Toga, stands on the the banks of the Thames in the borough of Westminster.

(www.historyhome.co.uk/peel/individuals/huskisso.htm)

William Huskisson was the son of William, the second son of William Huskisson of Oxley, near Wolverhampton. He was born at Birch Moreton Court, Warwickshire, on 11 March 1770. His mother, Elizabeth, daughter of John Rotton of Staffordshire, died in 1774, and in the following year William was sent to school, initial at Brewood, then at Albrighton in Staffordshire, and afterwards at Appleby in Leicestershire. At an early age he showed mathematical potential. In 1783 his maternal great-uncle, Dr. Gem, a nicely-known healthcare man residing in Paris, exactly where he had been doctor to the British embassy since 1762, undertook his education. For some years he lived at Paris in the society of French liberals, and created the acquaintance of Franklin and Jefferson. He is said to have entered Boyd & Ker’s bank in Paris for a time, but this is very doubtful. He was present at the fall of the Bastille, and in 1790 he joined the ‘Club of 1789,’ a monarchical constitutional club, ahead of which on 29 August 1790 he study a discourse on the currency, which was printed and a lot applauded. When the French government decided upon the problem of assignats he separated himself from this club. About the very same time he was introduced, by means of Dr. John Warner, the chaplain to the embassy, to Lord Gower (subsequently Marquis of Stafford), then British ambassador at Paris, whose private secretary he became. They remained intimate pals all their lives. On 10 August 1792, after the attack on the Tuileries, he was instrumental in enabling its governor, M. de Champcenetz, to make his escape from the populace. On the recall of the embassy in 1792 Huskisson returned to England. For some time he remained an inmate of Lord Gower’s household in England, and as a result became well acquainted with Pitt.

By the death of his father in 1790 he became entitled to such of the family members estates at Oxley in Staffordshire as remained unalienated, but they were neither in depth nor unencumbered, and, locating himself a poor man, he was glad to avail himself of the offer you of a new workplace, developed beneath the Alien Act, for making arrangements with the émigrés. In this employment, for which his understanding of the French individuals and language well fitted him, he became acquainted with Canning, and his talents advised him to Pitt and Dundas.

In 1795 he succeeded Sir Evan Nepean, on his promotion to be secretary to the admiralty, in the workplace of under secretary at war. The company of the office was virtually completed by Huskisson, Dundas, his chief, becoming otherwise occupied, and it was he who superintended the arrangements for Sir Charles Grey’s expedition to the West Indies. His friendship with Lord Carlisle procured him in 1796 the representation of Morpeth but, usually diffident of his personal skills and conscious that he was no orator, he did not speak in the Property of Commons until February 1798. In January 1801 he resigned with Pitt, but at the request of Lord Hobart, the new secretary at war, who was unfamiliar with the function of the office, he remained at his post till the battle of Alexandria in March 1801. An unfounded charge was produced at the time that Huskisson made use of his knowledge of official secrets in stockjobbing operations, in which he engaged with Talleyrand. Meantime, on the death of Dr. Gem in 1800, he inherited an estate at Eastham, Sussex, then occupied by Hayley, the biographer of Cowper, and yet another in Worcestershire. This rendered his position in public life unembarrassed.

In 1802 he contested Dover, but was beaten by Trevanion and Spencer Smith, the government candidates, and did not re-enter parliament till February 1804, when he was elected for Liskeard. There was a double return, and a petition was presented against him, but he kept his seat. On the recall of Pitt to workplace (Might 1804) he was appointed a secretary to the treasury, but when the ‘Talents’ administration came in (January 1806) he retired, and went into active opposition. He moved a quantity of monetary resolutions in July 1806, which the chancellor of the exchequer, Lord Henry Petty, was obliged to accept. At the general election in the autumn of 1807 he was again returned for Liskeard was created secretary to the treasury once again in the Duke of Portland’s ministry in April 1807 and at the ensuing basic election was returned for Harwich, which seat he retained till 1812.

Up to this time Huskisson had seldom engaged in general debate, but had rested content with his reputation as a man of business. In 1808 he took a massive share in the rearrangement of the relations between the Bank of England and the treasury, and in 1809 he undertook the reply to Colonel Wardle’s motion on public economy. In the identical year the Duke of Richmond, the Irish viceroy, was anxious that he need to succeed Sir Arthur Wellesley as chief secretary, but his solutions could not be spared by the English government. Although not personally concerned in the dispute which brought about Canning’s resignation in 1809, he resigned with him out of loyalty to his friend, and in his private capacity in parliament remained for some time small noticed. But in 1810 he published his pamphlet on the ‘Depreciation of the Currency,’ which at as soon as met with success and earned him the reputation of getting the 1st financier of the age. In the debates on the Regency Bill he adhered to Canning’s views, and in January 1811, when he was sounded about joining the regent’s ministry, he rejected the overture. In the following year, if Canning had joined Lord Liverpool, Huskisson would have been chief secretary to the viceroy and chancellor of the Irish exchequer. His adherence to Canning retarded the advance of his public profession by a lot of years, and permitted Peel and Robinson, of whom 1 was his junior and the other a lot his inferior, to pass him in the race. During this year he became colonial agent for Ceylon. That post, which was worth £4,000 a year, he held till 1823.

At the common election in the autumn of 1812 Huskisson was elected for Chichester. He created a number of speeches on currency concerns in March 1813, and on Sir Henry Parnell’s motion on the corn laws he brought forward for the very first time his scale of graduated prohibitory duties. Next year on six August he succeeded Lord Glenbervie, in Lord Liverpool’s ministry, in the woods and forests department, and was sworn of the privy council on 29 July 1814. He swiftly mastered the special duties of his office.

In 1815 was passed the 1st corn law, which totally prohibited the importation of corn when the cost fell under a specific minimum typical, and Huskisson took a prominent component in the debates on the bill. In Might 1816 he spoke in the bank restriction debates in favour of leaving to the bank the determination of the time, not to exceed two years, within which they may possibly continue the restriction on gold payments but two years afterwards he was in favour of granting the bank a further extension of time. He normally voted for Roman catholic emancipation without having speaking, and really seldom intervened in a debate on foreign policy. One of his rare speeches on general topics was produced in 1821 on Lord Tavistock’s motion for a vote of censure on the government for its behaviour to the queen. In 1819 he became a member of the finance committee, and his speech on the chancellor of the exchequer’s income and expenditure resolutions almost certainly saved the government from defeat. He also addressed to Lord Liverpool an critical memorandum on the resumption of money payments.

In 1821 he was a member of the committee appointed on Gooch’s motion to inquire into the prevalence of agricultural distress, and the report of the committee was principally drafted by him but his speeches on taxation in the same year gave rise, not unnaturally, to a distrust of him among the agricultural party, which was in no way afterwards removed. He felt his position in the government to be unsatisfactory, though he did not resign with Canning in that year, and when, at the finish of 1821, a rearrangement of the administration was projected and the Irish secretaryship was provided him, he at when refused the post. In February 1822 Huskisson spoke against Lord Londonderry’s proposal to lend £4,000,000 for the relief of agricultural distress, and on 29 April and 6 May possibly succeeded in defeating Lord Liverpool’s first resolution on the report of the committee on agricultural distress. Thereupon he tendered his resignation, which Lord Liverpool refused, and Huskisson shortly right after did outstanding service in fighting the country celebration single-handed on Western’s motion for a pick committee to inquire into the consequences of the resumption of cash payments, and carried an amendment in the terms of Montague’s resolution of 1696, ‘that this Property will not alter the standard of gold or silver in fineness, weight, or denomination’.

When Canning rejoined the ministry as foreign secretary in September 1822, he failed in an endeavour to receive for his buddy the presidency of the board of control, with cabinet rank. On 31 January, even so, Huskisson was promoted to the treasurership of the navy, and on five April to the board of trade, holding each offices with each other, and he was soon afterwards admitted to the cabinet. The board of trade was an workplace in which his particular understanding and his sophisticated free-trade opinions have been specific to make him conspicuous. Accordingly, as Canning was retiring from the representation of Liverpool, which he identified as well laborious for his new position, Huskisson was selected to succeed him as the only tory able to conciliate the Liverpool merchants, and soon after a hollow contest he was elected, 15 February 1823. Huskisson as a result became the prominent representative of mercantile interests in parliament. He was quickly active in office, and introduced a bill for regulating the silk manufactures, but owing to the sweeping character of the lords’ amendment he dropped it for that session, and did not pass it till 1824. He also introduced and passed a merchant vessels’ apprenticeship bill, a bill to remove the restrictions on the Scottish linen manufacture, and a registration of ships bill. He announced his intention of moving the repeal of the Spitalfields acts, and supported Joseph Hume’s motion for a select committee on the mixture laws, which led in the end to their repeal.

The year 1825 was one of great activity for him. With the assistance of James Deacon Hume of the board of trade, he completed the consolidation into eleven acts of the entire of the current revenue laws. He obtained a choose committee to inquire into the relations of employers and employed, the outcome of which was the passing of an act which regulated the relations of capital and labour for forty years. A single object of his policy was at the same time to give England cheap sugar and he also amended the income laws in the direction of a modified free trade in regard to other commodities, reducing the old duties on foreign cotton goods, which ranged from 50 to 75 per cent., according to top quality, to a uniform 10 per cent. duty on all qualities on woollen goods from 50 and 67¾ per cent. to 15 per cent., and equivalent reductions had been produced in the duty on glass, paper, bottles, foreign earthenware, copper, zinc, and lead.

Early in 1825 Huskisson foresaw the crisis to which excessive speculation was major. His warnings had been neglected, and when the panic came he was accused of obtaining triggered it by his policy of free trade. Meanwhile he was busily occupied in negotiations with the American government about the north-western boundary, the navigation of the St. Lawrence, and the slave trade. In 1826 the Liverpool merchants presented him, in acknowledgment of the accomplishment of his policy, with a service of plate. He took a prominent component in the debates on the Bank Charter and the Promissory Notes Acts, and on 24 February 1826 delivered what Canning known as ‘one of the extremely best speeches that I ever heard in the Property of Commons’ against Ellice’s motion for a committee on the silk trade. Later on, in speaking upon Whitmore’s motion for a committee on the corn laws, Huskisson, though advocating delay in their repeal, admitted his dislike of the current method. During the autumn he assisted Lord Liverpool in preparing a new corn bill. The labour thus involved, and the calumnies to which his economic policy had exposed him, permanently injured his wellness. On 7 Could he vindicated his commercial policy against the attacks created upon it by Gascoyne in his motion for a committee on the shipping interest. The speech, which was afterwards published, was one particular of his best efforts. His corn bill was duly introduced, but was abandoned owing to the opposition of the Duke of Wellington in the House of Lords.

Huskisson was travelling in the Tyrol to recruit his health when the news of Canning’s death reached him (August 1827). He hastened residence. At Paris a message from Lord Goderich, the new prime minister, offered him the colonial office, with the lead of the Residence of Commons. His friends urged that there was no other way of securing the continuation of Canning’s policy, and he accepted the supply on 23 September 1827. Had he selected he may have been chancellor of the exchequer. Dissensions quickly broke out among him and John Charles Herries, the chancellor of the exchequer, about the appointment of Lord Althorp as chairman of the committee of finance. Huskisson, as leader of the home, insisted upon his nomination Herries, as chancellor of the exchequer, complained that he had been slighted by not becoming previously consulted. The dispute grew so extreme that Lord Goderich resigned, and was succeeded by the Duke of Wellington.

Huskisson decided to continue in workplace, and was re-elected at Liverpool without opposition. In addressing his constituents he said that the duke had acceded to his stipulations in favour of the continuance of totally free trade and Canning’s foreign policy. The duke on the earliest chance denied this, and Huskisson was obliged to withdraw the statement in the Property of Commons on 18 February. The tension among himself and the duke quickly became acute. At many cabinets in March a difference of opinion arose on the amendment to the corn bill with regard to the taking of corn out of warehouse, which the duke proposed and insisted upon. Peel and Huskisson were both against it. Huskisson tendered his resignation, but a compromise which he recommended was accepted, and he remained in office. Shortly afterwards it became required to make a decision what must be done with the two seats which would be accessible for redistribution upon the disfranchisement of Penryn and East Retford for substantial corrupt practices. The duke was for giving both seats to the adjacent hundreds Huskisson, Palmerston, and Dudley were for bestowing them upon big manufacturing towns.

In the House of Commons Peel advocated a compromise by giving Penryn to Manchester and East Retford to the hundred. Huskisson on 21 March pledged himself to give one particular seat to a manufacturing town. In the lords it was decided by the government, first, not to deal with each situations together secondly, to give the Penryn seat to the hundred. In committee of the Property of Commons, when the East Retford case came up, it was moved on 19 Might to give that seat also to the hundred of Bassetlaw, Nottinghamshire. Huskisson and Palmerston, in the belief that the cabinet held that morning had resolved on leaving East Retford an open query, voted against the ministry. Immediately following leaving the home Huskisson wrote to the duke offering to resign if he regarded that the interest of the government would be much better served by a resignation. The duke had lengthy felt that Huskisson, who entered the administration as the successor to Canning’s position, was in some sort his rival. He treated Huskisson’s letter as an actual resignation, though Huskisson explained that he only meant to tender it if the duke thought fit to demand it, and he repudiated any formal offer you of resignation. But the duke was inflexible, and laid the matter ahead of the king. Huskisson demanded a personal audience of his majesty, but this was refused, and the resignation was definitively completed on the 29th, when he gave up the seals and received expressions of the king’s private regret at his loss. Although he explained in the Property of Commons the summary mode by which he had been removed, his celebration censured him for imperilling the ministry by an ill-timed and factious resignation.

Huskisson appeared tiny in parliament for the duration of the remainder of the session, and, his overall health failing, he spent the autumn abroad. In 1828 he supported the Roman Catholic Emancipation Bill created a fantastic speech on the silk trade, and took up the study of Indian queries. In consequence the governorship of Madras was presented him, and he was sounded about the governor-generalship of India, but the state of his overall health made his acceptance of either post impossible. He was, even so, an active member of the East India committee, especially on matters referring to the China trade. During the session of 1829 he was unusually prominent in debate. He produced many speeches in favour of moderate reform, warned the ministry that some change was inevitable, and supported Lord John Russell’s proposal to confer further parliamentary representation on Leeds, Liverpool, and Manchester. For the duration of 1830 his well being grew worse, and, though he was capable to attend the king’s funeral in July, he was seriously ill.

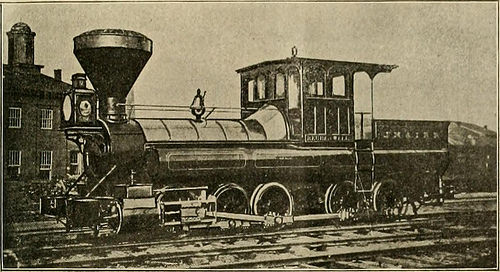

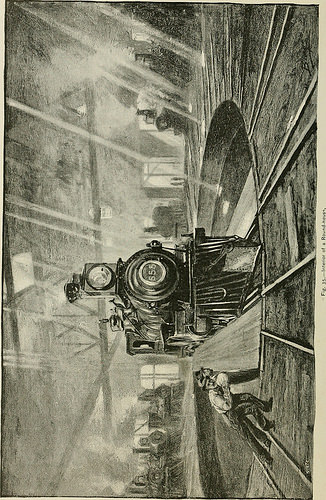

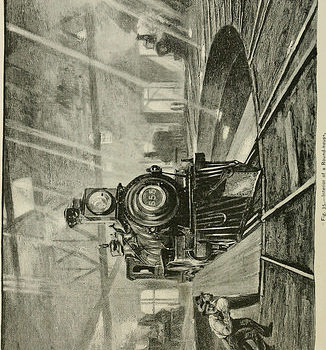

He went to Liverpool in September for the opening of the Manchester and Liverpool railway, and was received warmly by his constituents. On 15 September he attended the opening ceremony. A procession of trains was run from Liverpool. Parkside was reached without mishap. There the engines stopped for water, and the travellers, contrary to directions, left the carriages and stood upon the permanent way, which consisted of two lines of rails. Huskisson went to speak to the Duke of Wellington, to whom, in spite of their current disagreement, he felt bound, as member for Liverpool, to show courtesy. At that moment several engines were seen approaching along the rails amongst which Huskisson was standing. Everybody created for the carriages on the other line. Huskisson, by nature uncouth and hesitating in his motions, had a peculiar aptitude for accident. He had dislocated his ankle in 1801, and was in consequence slightly lame. Thrice he had broken his arm, and following the last fracture, in 1817, the use of it was permanently impaired.

On this occasion he lost his balance in clambering into the carriage and fell back upon the rails in front of the Dart, the advancing engine. It ran over his leg he was placed upon an engine and carried at its utmost speed to Eccles, where he was taken to the home of the vicar. He lingered in fantastic agony for nine hours, but gave his last directions calmly and with care, expiring at 9 p.m. He was buried with a public ceremonial in Liverpool on the 24th.

Huskisson accomplished small achievement in public life compared with that which his rare skills must have commanded. His adherence to Canning, combined with a coldness of manner, possibly accounts for a lot of his failure. Lamb, afterwards Lord Melbourne, told Greville that, in his opinion, Huskisson was the greatest sensible statesman he had identified, the one particular who ideal united theory with practice. Sir James Stephen’s judgment on him was practically the identical. As a speaker he was luminous and convincing, but he produced no pretence to eloquence his voice was feeble and his manner ungraceful. Sir Egerton Brydges, in his Autobiography speaks of him as ‘a wretched speaker with no command of words, with awkward motions, and a most vulgar, uneducated accent,’ but this accent seems to have worn off in later life.

Greville describes him as ‘tall, slouching, and ignoble-looking. In society extremely agreeable without having considerably animation usually cheerful, with a great deal of humour, data, and anecdote gentlemanlike, unassuming, slow in speech, and with a downcast appear as if he avoided meeting anybody’s gaze. There is no man in parliament, or perhaps out of it, so well versed in finance, commerce, trade, and colonial matters it is nonetheless remarkable that it is only within the last 5 or six years that he acquired the excellent reputation which he latterly enjoyed. I do not think he was looked upon as more than a second-price man, till his speeches on the silk trade and the shipping interest, but when he became president of the board of trade he devoted himself with indefatigable application to the maturing and lowering to practice these commercial improvements with which his name is linked, and to which he owes all his glory and most of his unpopularity.’

He married, on six April 1799, Elizabeth Mary, younger daughter of Admiral Mark Milbanke, who survived him. There was no problem of the marriage. Even though so impoverished on getting into public life that he sold the loved ones estate at Oxley, his personalty was sworn, 15 November 1830, below £60,000. He received on 17 May 1801 a pension of £1,200 per annum, nominal, £900 actual, with a remainder of £615 to his widow and in 1828 he received a second pension of £3,000 a year.

There is a plaque on the spot exactly where the accident occurred that reads:

THIS TABLET

A TRIBUTE OF Personal RESPECT AND AFFECTION

HAS BEEN PLACED Right here TO MARK THE SPOT Exactly where ON THE

13TH. OF SEPT. 1830 THE DAY OF THE OPENING OF THIS RAILROAD

THE Proper HONBLE. WILLIAM HUSKISSON M.P.

SINGLED OUT BY THE DECREE OF AN INSCRUTABLE PROVIDENCE FROM

THE MIDST OF THE DISTINGUISHED MULTITUDE THAT SURROUNDED HIM.

IN THE Complete RIDE OF HIS TALENTS AND THE PERFECTION OF HIS

USEFULNESS MET WITH THE ACCIDENT THAT OCCASIONED HIS DEATH,

WHICH DERIVED ENGLAND OF AN ILLUSTRIOUS STATESMAN AND

LIVERPOOL OF ITS MOST HONOURED REPRESENTATIVE WHICH CHANGED

A MOMENT OF THE NOBLEST EXULTATION AND TRIUMPH THAT SCIENCE AND

GENIUS HAD EVER Achieved INTO One OF DESOLATION AND MOURNING

AND STRIKING TERROR INTO THE HEARTS OF ASSEMBLED THOUSANDS,

BROUGHT Property TO Each BOSOM THE FORGOTTEN TRUTH THAT

“IN THE MIDST OF LIFE WE ARE IN DEATH”

(Stephen, Sir Lesley & Lee, Sir Sidney (eds.). (1949) ‘Dictionary of National Biography: from the earliest instances to 1900’. Oxford University Press, London.)

Huskisson lived at Eartham Property, Eartham, buying the residence from the poet, William Hayley."

![Image from web page 342 of “Railway master mechanic [microform]” (1895) Image from web page 342 of “Railway master mechanic [microform]” (1895)](http://www.precisiontype.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/14761630565_a4c5a2b09c-500x350.jpg)