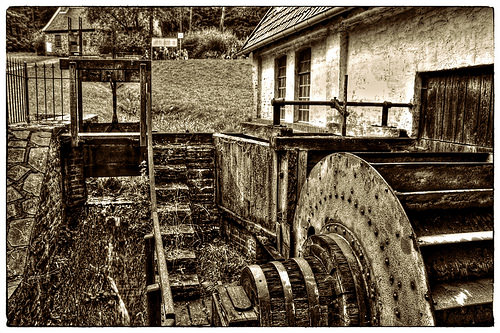

A couple of good milling engineering images I identified:

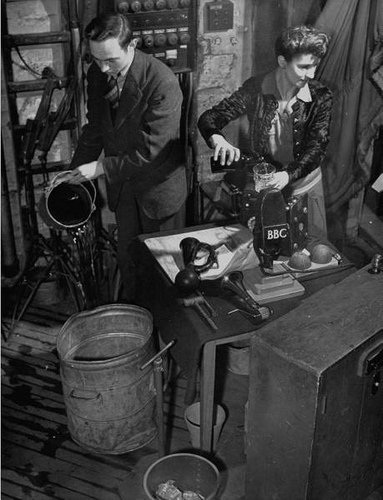

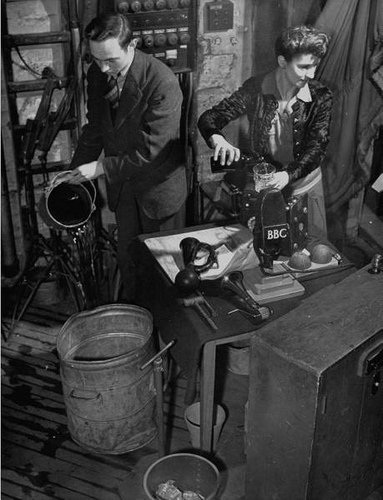

sound effects that made Tv history

Image by brizzle born and bred

image above: Two veterans of the Workshop recreate some of its renowned sounds.

The BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop, a pioneering force in sound effects, would have been 50 this month. Ten years following it was disbanded, what remains of its former glory?

Deep in the bowels of BBC Maida Vale studios, behind a door marked B11, is all that is left of an institution in British television history.

A green lampshade, an immersion tank and half a guitar lie forlornly on a shelf, above a couple of old synthesisers in a area complete of electrical bric-a-brac.

These are the sad remnants of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, set up 50 years ago to develop revolutionary sound effects and incidental music for radio and tv.

The corporation initially only offered its founders a six-month contract, simply because it feared any longer in the throes of such creative and experimental workout routines may make them ill.

Using reel-to-reel tape machines, early heroines such as Daphne Oram and Delia Derbyshire recorded everyday or strange sounds and then manipulated these by speeding up, slowing down or cutting the tape with razor blades and piecing it back together.

The sound of the Tardis was 1 sound engineer’s front-door key scraped across the bass strings on a broken piano. Other impromptu props integrated a lampshade, champagne corks and assorted cutlery.

Ten years ago the workshop was disbanded due to charges but its reputation as a Heath Robinson-style, pioneering force in sound is as powerful as ever, acknowledged by ambient DJs like Aphex Twin.

Although considerably of its gear has lengthy been sold off, each and every sound and musical theme it produced has been preserved. To mark its 50 years, there are plans for a CD box-set.

Right here Dick Mills and Mark Ayres, who each worked there, use the surviving gear to revive four sounds from the previous.

Green Lampshade

This was a stroke of genius from Delia Derbyshire, who died in 2001 and famously created the Medical doctor Who theme tune from Ron Grainer’s score.

The magic of Delia Derbyshire’s lampshade, recreated by Dick Mills and Mark Ayres

She would hit the tatty-seeking aluminium lampshade to create a sound with a organic, pure frequency. Right after recording it on tape, she would play with it to make the desired sound effect.

For a documentary on the Tuareg people of the Sahara desert, she took the ringing element of the lampshade sound, faded it up and then reconstructed it utilizing the workshop’s 12 oscillators to give a whooshing sound, allied to her own voice.

"So the camels rode off into the sunset with my voice in their hooves and a green lampshade on their backs," she once said.

The green lampshade has because gained close to-mythical status and Peter Howell, who succeeded Derbyshire in the early 1970s and reworked the Medical professional Who theme tune, can see why.

"It’s a helpful point to cling on to simply because every person knows what a lampshade is due to the fact it symbolises the use of domestic objects to produce sounds."

The workshop fascinates his music students nowadays simply because of all the kit employed back then, he says, and its influence is nonetheless clearly observed – an advert for a VW Golf that makes use of only sounds of the vehicle, for instance.

"The sampling era we’re now in is the subsequent generation of the same principle."

Dalek Voice

The sound that sent youngsters, and many adults, cowering behind sofas was co-produced by Mills, a sound engineer who joined the workshop in its initial year and left 35 years later.

Generating the voice of the Daleks

"We tried to give the impression that whenever a Dalek spoke, it wasn’t speaking like we do, it was accessing words from a memory bank, so they all sound the same – dispassionate, mechanical and retrievable."

He utilised a centre-tap transformer plugged into the microphone of an actor standing at the side of the set, and the threat in the voice was all in the overall performance.

Sometimes the tape got played at the wrong speed and the voice came out slightly differently, but the arrival of the EMS VCS3 synthesiser in the late 60s did not signal the end for this tried and tested strategy.

In other methods, nevertheless, the synthesisers changed the way the workshop operated and – in spite of some resistance by individuals – presented a larger selection.

Workshop Highlights

Sound effects: Quatermass and the Pit, The Goon Show, Blake’s 7, The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, Doctor Who Music: Woman’s Hour, Tomorrow’s World, Blue Peter, John Craven’s Newsround, Medical doctor Who

"Synthesisers provided a wide open pallet of colours and sounds to play with, but you still had to pick what you wanted to do and learn the discipline of this new technological type," says Mills.

"So on the one hand, it was effortless but you still had the original difficulty of considering of the idea in the 1st place."

Sci-Fi Door Opening

Sci-fi fans will recognise the "swooshing" door from programmes such as Physician Who and Blake’s 7, plus in the odd hotel scene in other programmes.

The workshop’s suitcase synth

The suitcase synthesiser was a portable version of the VCS3, useful for jobs out of the studio.

Recalling the early days and influences, Mills says: "We would take a pre-recorded sound effect from the BBC’s vast library but treated them to produce cerebral effects. If you wanted a character to seem to be thinking, you got him to read the line and put in a strange echo."

Related tactics had been already utilized in Europe in "musique concrete".

"They did it for their own investigation and study, but our way of life was we never did something until a commission.

So all our experimentation and investigation was taking place in the context of that radio or tv programme."

One of Mills’ proudest creations was the slimy monster sound, which was him spreading Swarfega cleaning gel on his hands and then slowing down the sound.

And he produced the upset tummy of Major Bloodnok in The Goon Show, a colonial officer who liked curry, by utilizing burp sounds and an oscillator to give a violent, explosive gastro-effect. Making use of contrasting sounds extremely speedily is a trick in audio comedy.

"We did our personal factor in the name of artistic creation. Functioning here was a bit like surf riding. Every so typically a creative wave of power kept you going till the wave ran out."

Broken Guitar

1 pluck of a guitar string became the well-known Dr Who bass line. Derbyshire and Mills sped it up and slowed it down to get the different notes, and these had been cut to give it an further twang on the front of each note.

Demonstration of the Radiophonic Workshop’s guitar

"It slides up to the note each and every time if you listen meticulously," says Mills. "Delia fabricated the baseline out of two or 3 lines of tape.

"You’d be scrabbling around the floor saying ‘Where’s that half-inch of tape I wanted to play on the front of that note?’"

Every single sound generated by the workshop and employed in radio or tv is preserved, partly in thanks to archivist Mark Ayres, who worked there whilst a student.

He believes a single of its greatest legacies is that it created listeners much more utilised to hearing such sounds as portion of everyday entertainment and education.

"It led to] the steady integration of experimental sound into popular culture and the placement of such sound into the mainstream rather than it becoming confined to various strictly academic studios.

"Certainly, considerably of this took place in parallel with developments elsewhere – The Beatles’ Sergeant Pepper and Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon for example.

"Later on, the workshop housed a couple of the most advanced laptop-primarily based MIDI studios in the globe, but by that time competition from the outside world was too fantastic and, under [the BBC’s policy] Producer Decision, the workshop could not compete on price and its demise was inevitable."

Old Mills and Guthrie along the Mississippi

Image by Gmonkey

PA – Mill Run: Fallingwater

Image by wallyg

The cantilevered terraces are crucial to the organization and knowledge of Fallingwater, uniting the indoor and outside space.

Fallingwater, at times referred to as the Edgar J. Kaufmann Sr. Residence or just the Kaufmann Residence, situated inside a five,one hundred-acre nature reserve 50 miles southeast of Pittsburgh, was created by Frank Lloyd Wright and built between 1936 and 1939. Built more than a 30-foot flowing waterfall on Bear Run in the Mill Run section of Stewart Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania, the property served as a vacation retreat for the Kaufmann family members such as patriarch, Edgar Kaufmann Sr., was a effective Pittsburgh businessman and president of Kaufmann’s Department Retailer, and his son, Edgar Kaufmann, Jr., who studied architecture briefly below Wright. Wright collaborated with employees engineers Mendel Glickman and William Wesley Peters on the structural design, and assigned his apprentice, Robert Mosher, as his permanent on-web site representative throughout construction. Despite frequent conflicts amongst Wright, Kaufmann, and the construction contractor, the home and guesthouse had been ultimately constructed at a price of 5,000.

Fallingwater was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1966. It was listed amongst the Smithsonian’s 28 Locations to See Before You Die. In a 1991 poll of members of the American Institute of Architects (AIA), it was voted "the greatest all-time work of American architecture." In 2007, Fallingwater was ranked #29 on the AIA 150 America’s Favourite Architecture list.

National Register #74001781 (1974)